THE DEATH OF DIANE SMITH- SHORTY’S STORY

Accused and tried for Diane Smith’s murder; Shorty’s story

Sunday, March 31, 2013

For years it was rumoured that Dennis ‘Shorty’ Jenkins — the man who was charged with the rape and murder of Diane Smith — was shipped off to the USA after his acquittal and then killed. In 2003, then Jamaica Observer writer Pat Roxborough-Wright (now deceased) found Jenkins and interviewed him. Here is a reprint of the story, headlined ‘Shorty alive and well’, as it appeared in the February 9, 2003 edition of the Sunday Observer.

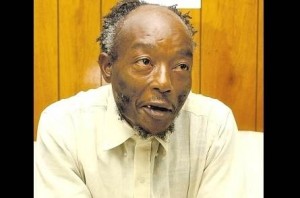

Dennis ‘Shorty’ Jenkins telling his story to the Observer in February 2003.

1/1

Dennis ‘Shorty’ Jenkins was killed almost 20 years ago in the United States, stuffed into a barrel and shipped back to Jamaica within months of being acquitted of the murder of Diane Smith, a student of the Immaculate Conception High School for girls.

That, for many Jamaicans, was the closing chapter of one of the most sensational and widely publicised murder mysteries, as a dead Shorty could tell no tales about who really raped, stabbed and strangled the schoolgirl on May 4, 1983.

Where that rumour came from is anyone’s guess. Defence attorney Earl Witter said he first heard it at a party in New York in 1985, months after the trial. Several other people said they just, well, heard and accepted it.

But Jenkins, who, apart from a splinter in his left foot, enjoys good health at the age of 52, has never held a passport much more a visa, never left Jamaica and, based on what he told the Sunday Observer last week, doesn’t have a clue who committed the crime.

“Furthest me ever go inna mi life is Palisadoes, follow mi family go airport,” he said, chuckling.

That was the opening line of a more than 60-minute storytelling session that brought his friend and lawyer, Bert Samuels, close to tears at points, but for the most part had his audience laughing.

Not that it was a particularly funny story — Jenkins spent two years and 10 days in jail between his arrest and acquittal — but as the diminutive man lost his initial shyness and got into the story with raw, frank and colourful ruralness, it became impossible to keep a straight face.

Take his rebuttal of the gonorrhoea label.

Samuels had been struggling to find a polite way of making the point that the bacteria which led the prosecution’s forensic expert to say that Jenkins had the venereal disease was actually gonnococus, the bacteria that gives rise to the disease.

Midway through his explanation, though, Shorty took the reins.

“What happen is that me neva bathe fi ’bout three days when them arrest me and me never get fi use the bathroom so you know the custard that form ‘roun mi hood drum (tip of the penis), dem say that was the gonorrhoea. But when me hear dem say it inna court mi jump up and ask how come mi private nuh rotten off, mi nuh have no gonorrhoea, me nuh go doctor from the time mi inna prison, so how me hood nuh rotten yet.”

And he was right, Samuels concluded.

“We asked a doctor and he confirmed that if Shorty really had gonorrhoea he would have suffered damage to that area if it had gone untreated for that time,” he said.

By then, Jenkins had taken charge of the conversation. The gonorrhoea wasn’t the only issue he wanted to talk about on the nostalgic trip back to the day he was arrested. There was the confession he swore he never made to his cell-mates, the pubic hairs that were taken from him in the attempt to produce evidence linking him to the crime, the disruption to his life caused by the episode, the shame, the abuse, the scorn he had to endure before being acquitted by a 12-member jury at the end of a retrial that lasted over two weeks.

The frightening thing about the story as Jenkins told it, is that it could have happened to anyone who had been in what turned out to be the wrong place at the wrong time.

There were no eyewitnesses and, as it turned out, no reliable evidence linking Jenkins or his co-accused, Leroy Wallen, a 35-year-old bus baggageman, to the crime.

Wallen was released at the end of a no-case submission by his lawyers Jack Hines and Hensley Williams, who in turn, teamed up with Jenkins’ lawyers.

Shorty’s defence was that on the morning of the murder he had made his customary trip to the ackee walk in Constant Spring, picked a bag of the fruit, sold it to a Rastafarian, and went home to babysit his sister’s four children — two girls and two boys.

In the evening, on his way home, he stopped to rest by an old car in Constant Spring. “A man ask mi ’bout him pig dem an me tell him mi neva see them. He ask me if me hear what happen to the schoolgirl. Me say no,” recalled Jenkins.

Before he knew what was happening, the police had locked him up.

“Dem lock me up wid some prisoner and dem almost murder me in deh. Seh mi a wicked bwoy because look what me do the nice, nice girl. Next ting when the police come dem draw a card pan me and tell police seh me seh me see the dead girl inna di gully and sex the body. But nutten neva go so, me neva seh so,” he told the Sunday Observer.

“It wasn’t just Shorty on trial,” said Witter, who led Jenkins’ defence team at Samuels’ invitation. “It was the entire justice system.”

And if ever there was a case to bolster the argument that the justice system can work independently of financial and social clout, it was Jenkins’ murder trial.

For Jenkins — a poor 34-year-old man, who, after a year-and-a-half of being unable to find work in the construction industry, began to pick and sell ackees for a living — didn’t have the first dollar with which to fund a defence team. He had to rely on legal aid and the efforts of Samuels, who was just three years out of law school.

“I had known Shorty since I was 14,” said Samuels. “His sister used to work with my mother. We lived within minutes of each other. So when this thing happened, they came to me for help.”

With the help of K D Knight, the lawyer-turned-politician, Samuels managed to convince just one of the 11 jurors — a woman — that Jenkins was not the rapist/murderer. That paved the way for the retrial, which saw Witter leading Samuels, his sister, Jackie Samuels-Brown, Hines, and Williams in Jenkins’ defence.

It was a close call, but Jenkins, who told the Sunday Observer that he had never imagined going to the gallows for a crime he knew he didn’t commit, didn’t seem worried.

“Me tell them not to worry, we will appeal if we lose the case because it wasn’t me,” he said. “The only thing I was afraid of was the locking up.”

His simplistic confidence frightened the defence team, which understood only too well the dangerous implications that the case’s massive publicity held for Jenkins.

“Here you had the whole country calling for Shorty’s blood. Literally, the mood was similar to what obtained in America at the time when schools were being desegregated,” said Samuels.

“There was a lot of anger, hatred and violence directed at Shorty and us too. When we were walking to the courthouse there were people on every side screaming at us to bring Shorty. One woman said, ‘gi him to we mek we rip him up and nyam him’… once Shorty’s mother came to the courthouse. It was the first and last time. Somebody pointed her out and the crowd attacked. I had to whisk her off into a taxi with the help of a policeman. This was the background against which Shorty was expressing confidence.”

“You’d have to be there to understand,” said Witter. “Shorty had this way of smiling as if his innocence was enough. We had to be telling him for his own safety, not to infuriate people by waving from the paddy wagon and that sort of thing.”

In an attempt to ensure that Shorty got a fair trial, the lawyers applied for a change of venue. But nothing, including the near mauling of Jenkins’ mother, could convince the judges of the day to move the trial. It took place at the Supreme Court inspite of the jeering mob that followed the proceedings from start to finish.

The day of the verdict was a momentous one for Jenkins.

“The morning I get up and pick some ackee down by GP to show people what really happened. I am a fruit picker. I walk with the ackee, that I am innocent,” he said.

If Jenkins had been privy to what went on in the jury room where his fate was decided, he may have been a tad less confident. “It was an even split at the beginning of the deliberations, six said guilty, six said not guilty,” Samuels told the Sunday Observer. “That’s what the forewoman told us after the trial.”

According to the forewoman, a well-to-do white woman who didn’t fit any of the criteria which the defence team had used to poll the jury with a view to eliminating persons of demonstrable or potential bias, not one of the six who instinctively wrote ‘guilty’ could spell the word correctly. The others who vouched for Shorty’s innocence were the more educated of the lot.

It was a far more tumultuous day for his lawyers. “I couldn’t help myself. I cried when the verdict came in,” said Samuels.

For Witter, who still had to be looking out for Jenkins in the immediate aftermath of the verdict — he was put in the lock-up even after the judge, UD Gordon, said he could go — the tears came months later in the year while dining at the Trade Winds Restaurant in downtown Kingston.

“I was sitting there, having lunch when I looked up. There was Shorty with a breadfruit in one hand and a bunch of bananas in the other. ‘This is for you, Mr Witter. Thanks,’ he said. It was the nearest I came to receiving any sort of pay for doing the trial. Nearly couldn’t finish the meal,” he said.

When Jenkins revels in the memories, however, he is full of smiles.

To him, David Nippez, the expert who confounded the opinions of Yvonne Cruickshank, the Government’s forensic analyst whose evidence, if accepted by the jury, would have sent him to the gallows, is remembered as ‘the white man’.

Defence attorney Winston Spaulding, the then attorney-general who helped the defence team procure the service of Nippez, is remembered in name only.

Director of Public Prosecutions Kent Pantry, then a prosecutor in the department, is remembered vaguely as a clear-skinned man who said “whole heap a things”.

Knight is remembered as the nice, quiet man who “musi did vex when di people never answer the verdict fi the first trial and go tek up politics”.

He remembers the other lawyers and would like to tell them thanks, only he doesn’t know how to contact them. All that’s left of the affair is a very entertaining story and the idlest of hopes that compensation, in the form of, say, a million dollars or even half of that, may come in somehow so that he can build a small house and a shop.

Read more: http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/Accused-and-tried-for-Diane-Smith-s-murder–Shorty-s-story_13977720#ixzz2P8VuAcJO

13 Responses to THE DEATH OF DIANE SMITH- SHORTY’S STORY

****RULES**** 1. Debates and rebuttals are allowed but disrespectful curse-outs will prompt immediate BAN 2. Children are never to be discussed in a negative way 3. Personal information eg. workplace, status, home address are never to be posted in comments. 4. All are welcome but please exercise discretion when posting your comments , do not say anything about someone you wouldnt like to be said about you. 5. Do not deliberately LIE on someone here or send in any information based on your own personal vendetta. 6. If your picture was taken from a prio site eg. fimiyaad etc and posted on JMG, you cannot request its removal. 7. If you dont like this forum, please do not whine and wear us out, do yourself the favor of closing the screen- Thanks! . To send in a story send your email to :- [email protected]

Leave a Reply